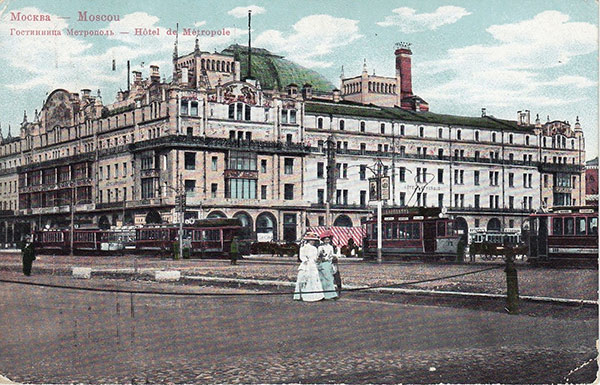

A Gentleman in Moscow Epigraphary

Click image to enlarge

To inhabit a place like the Kremlin is not to reside, it is to defend one’s self. Oppression creates revolt, revolt obliges precautions, precautions increase dangers, and this long series of actions and reactions engenders a monster; that monster is despotism, which has built itself a house at Moscow. The giants of the antediluvian world, were they to return to earth to visit their degenerate successors, might still find a suitable habitation in the Kremlin.

–Marques de Custine: The Empire of the Czar (1839)And to this day the Russian people, in spite of the stern and prosaic reality around them, like to believe in the seductive legends of long ago – and it may be years and years before they renounce this faith.

–Ivan Goncharov: Oblomov (1859)Reasonably intelligent individuals are never hoodwinked individually. But they possess another, equally harmful form of this human frailty: they are subject to mass delusion. A swindler will never be able to lead a single individual by the nose; but as for a large group taken together, their noses are always ready and willing! Meanwhile, the swindlers, weak as individuals and each led by his own nose, when taken together can never be led by their noses. That’s the whole secret of world history. But there’s really no need to delve into world history here. We’re telling a tale, so let’s get on with it.

–Nikolai Chernyshevsky: What Is to Be Done? (1863)I knew a gentleman who prided himself all his life on being a fine judge of Lafite. He regarded it as his positive merit and never doubted himself. He died not merely with a serene but with a triumphant conscience, and he was perfectly right.

–Fyodor Dostoevsky: Notes from the Underground (1864)Life meanwhile, people’s real life with its essential concerns of health, illness, work, rest, with its concerns of thought, learning, poetry, music, love, friendship, hatred, passions, went on as always, independently and outside of any political closeness or enmity with Napoleon Bonaparte and outside all possible reforms.

–Alexander Tolstoy: War and Peace (1869)Nothing, nothing is certain, except the insignificance of everything I can comprehend and the grandeur of something incomprehensible…

–Alexander Tolstoy: Prince Andrey in War and Peace (1869)Precisely because we are a broad, Karamazovian nature—and this is what I am driving at—capable of containing all possible opposites and of contemplating both abysses at once, the abyss above us, an abyss of lofty ideals, and the abyss beneath us, an abyss of the lowest and foulest degradation.

–Fyodor Dostoevsky: Brothers Karamazov (1880)My mother is a born Muscovite and unites within herself the qualities which to me symbolize Moscow: external, striking beauty, serious and strict through and through; aristocratic simplicity; inexhaustible energy; a unique union of tradition with true free thinking, woven out of great nervousness, imposing majestic calm, and heroic self-mastery.

–Wassily Kandinsky: Reminiscences (1913)This curious conglomeration of palaces, towers, churches, monasteries, chapels, barracks, arsenals and bastions, this incoherent jumble of sacred and secular buildings, this complex of functions as fortress, sanctuary, seraglio, harem, necropolis and prison, this blend of advanced civilization and archaic barbarism, this violent contrast of the crudest materialism and the most lofty spirituality – are they not the whole history of Russia, the whole epic of the Russian nation, the whole inward drama of the Russian soul?

–Maurice Paléologue: An Ambassador’s Memoirs (1914-1917)The Russian people are like children. One must love them and govern them well.

–Vaslav Nijinksy: The Diary of Vaslav Nijinksy (1919)Yes, we have all had to undergo a great deal of change, your country more than any: but even if we do not live to see it at its resurrection, the profound, the real, the other surviving Russia has only fallen back on her secret root system, as she did before, under the Tatar yoke, who could doubt that she is still there and is gathering her forces in that dark place, invisible to her own children, leisurely with her own sacred slowness, on to a possible still-remote future?!

–Rainer Maria Rilke: Letter from Rainer Maria Rilke to Leonid Pasternak (1926)

(Fearing political consequences, Lydia Pasternak deleted this passage when she sent a transcription of Rilke’s letter to her brother Boris who was still living in Moscow.)The woods fell away in the distance and the river wandered off in another direction. As the lorry drove on the scenery slowly changed: fences, a watchman’s hut, piles of logs, dried and split telegraph poles with bobbins strung on the wires between them, heaps of stones, ditches—in short, a feeling that Moscow was about to appear round the next corner and would rise up and engulf them at any moment.

–Mikhail Bulgakov: The Master and Margarita (1928-1940)Only in Russia is poetry respected, it gets people killed. Is there anywhere else where poetry is so common a motive for murder?

–Osip Mandelstam (1930s)Poets can never be indifferent to good and evil, and they can never say that all that exists is rational.

–Nadezhda Mandelstam: Hope Against Hope (1970)Own only what you can always carry with you: know languages, know countries, know people. Let your memory be your travel bag. Use your memory! Use your memory! It is those bitter seeds alone which might sprout and grow someday. Look around—there are people around you. Maybe you will remember one of them all your life and later eat your heart out because you didn’t make use of the opportunity to ask him questions. And the less you talk, the more you’ll hear.

–Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Gulag Archipelago (1973) His advice to prisoners in transit.