The Metropol

Click image to enlarge

A BRIEF HISTORY

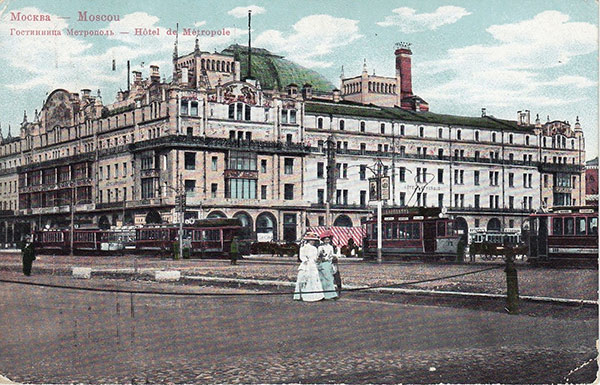

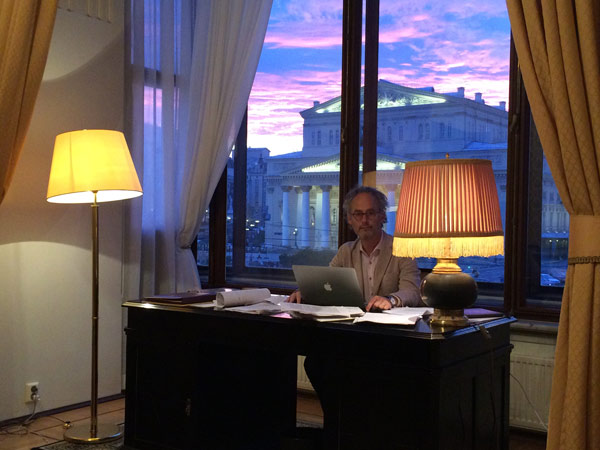

Opened in 1905, the Metropol Hotel is situated on Theatre Square in the historic heart of Moscow. Like the other grand hotels of the era (such as the Waldorf Astoria in New York, Claridge’s in London, and the Ritz in Paris), the Metropol set the standard in its city for luxury and service. It was the first hotel in Moscow to have hot water and telephones in the rooms, international cuisine in the restaurants, and an American bar off the lobby. Thus, within days of its opening, the Metropol became the preferred stomping ground not only for cosmopolitan travelers, but for the glamorous and well-to-do of the city.

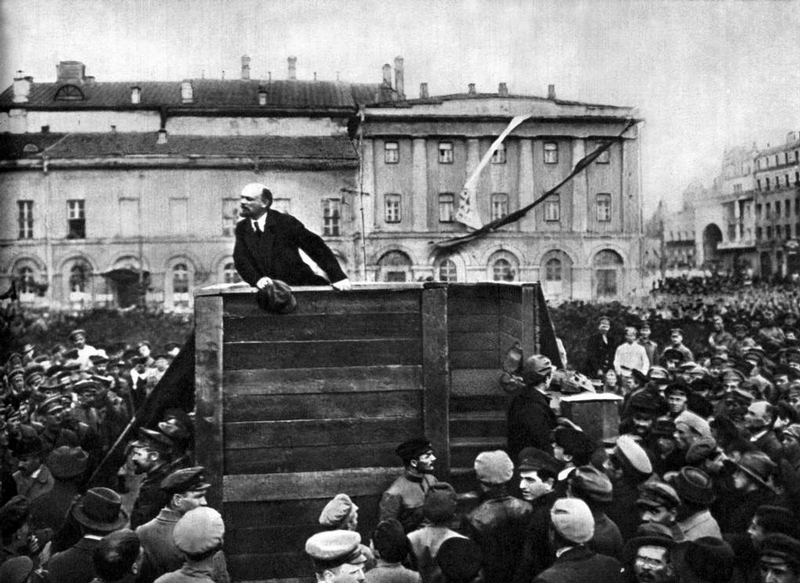

But just twelve years later the Metropol found itself serving as a bastion in a pitched battle with forces loyal to the Tsar defending the eastern flank of the Kremlin from the hotel’s suites, while the Bolsheviks returned fire from the streets below. In the ensuing battle nearly every window in the hotel was shattered. In fact, when American journalist John Reed arrived in the city (shortly after witnessing the fall of the Hermitage), he was assured by the Metropol’s unflappable front desk captain: “We have some very comfortable rooms, if the gentleman does not mind a little fresh air…”

When the victorious Bolsheviks decided to return the capital to Moscow (after 300 years in St. Petersburg), the city did not have the necessary infrastructure to house the new government. So, the Bolsheviks seized the Metropol, threw out the guests, renamed it the Second House of the Soviets, and used it to billet officials and house various departments of the fledgling state. In fact, it was in Suite 217 of the Metropol that Yakov Sverdlov, the first chairman of the All-Russia Executive Committee, locked the constitutional drafting committee, vowing he wouldn’t turn the key until they’d finished their work. Within a measure of hours the committee reemerged with that document which officially heralded the victory of the Proletariat over the forces of privilege.

Right then and there the Metropol’s existence as a grand hotel should have come to an end. But when the major European nations began restoring trade and diplomatic relations in the 1920s, the Bolsheviks realized that the hotels of Moscow were going to provide Western visitors with their first impression of the new Russia. Should weary ambassadors or businessmen spend their visit in some austere hostel with shared bathrooms, humble furnishings, and limited services, they might draw the conclusion that Communism was failing! So, in order to signal success, the Bolsheviks found themselves kicking out the apparatchiks and restoring the Metropol to its original glory complete with uniformed bellhops in the lobby, silver service in the restaurants, and American jazz in the bar.

Within a matter of years, “the Metropol was the new social center for the bourgeois colony,” recalled Eugene Lyons, the United Press’s Moscow correspondent in the early 1930s. “Its main restaurant was a Russian peasant’s dream of capitalist splendors—immense candelabra, oversized lights, heavy furniture, a jazz band of symphony orchestra proportions… The chief pride of the restaurant, its ultra-bourgeois touch, was a great circular pool where lights and rather proletarian-looking fishes played. On grand occasions, the chef in cap and apron emerged from his sanctum with a net over his shoulder and captured a fish for a special valuta [foreign currency] client. The dancing couples rotated around the pool, and sometimes an unsteady customer joined the fishes to the great delight of the assembled crowd…”

Thus, during those initial decades of the Soviet Union, which were characterized for the citizenry by all manner of hardship, the Metropol earned a mystique of extravagance equal to that of the Plaza or the Ritz—despite being around the corner from the Kremlin and a few blocks from the Lubyanka (the dreaded headquarters of the secret police). With its fine food, lavish entertainment, and liberal behavior, the hotel became something of an Oz in the popular imagination—a Technicolor paradise hidden in the midst of a black and white metropolis. Although, for this very reason, the hotel also became a popular trolling ground for the secret police who came in search of loose-lipped Westerners or compromised Russians.

What follows is a brief chronology of citations describing life in the Metropol from various memoirs and Russian novels. Close readers will note that some of these citations have been collaged into my depiction of the hotel.

1905

“I had to sing Dubinushka—not because I was asked to, but because the Tsar in a special manifesto had promised freedom. It was in Moscow, in the huge restaurant hall of the Metropol…All Moscow was celebrating that evening! I stood on the table and sang, full of excitement, full of joy!”

–Fyodor Shalyapin, the great Russian opera singer following Nicholas II’s (doomed) promise of liberal reforms

1917-1920

“Desperate fighting had broken out again in Moscow. The yunkers and White Guards held the Kremlin and the center of the town, beaten upon from all sides by the troops of the Military Revolutionary Committee. The Soviet artillery was stationed in Skobeliev Square, bombarding the City Duma building, the Prefecture, and the Hotel Metropol. The cobblestones of the Tverskaya and Nikitskaya had been torn up for trenches and barricades. A hail of machine-gun fire swept the quarters of the great banks and commercial houses. There were no lights, no telephones; the bourgeois population lived in the cellars…”

–John Reed, American journalist Ten Days that Shook the World“The Hotel Metropol was pitted with the marks of shells; dust was swirling and it was surprising to see, in the middle of the rubbish-littered, filthy square, a bed of bright flowers, planted there by someone for some incomprehensible reason…

The great hall of the restaurant in the Metropol, damaged by the October bombing, was not in service. However, they still served food and wine in private rooms, because part of the hotel was occupied by foreigners, mostly Germans and desperate businessmen who had managed to get themselves foreign passports… In the private rooms there were wild drinking bouts, as there had been in Florence during the time of the plague. Muscovites could also come inside by the back entrance, as long as they knew the right person. The Muscovites there were mostly actors, convinced that the Moscow theatres were not going to survive until the end of the season. They saw only doom and disaster ahead, and were drinking as if there was no tomorrow.”

–Alexei Tolstoy, Russian novelist Road to Calvary Part II

When, from the dusty ornamental style of the international hotel Metropol, after wandering under the high glass roof and along the corridors which make up the streets of this indoor city, stopping from time to time at the barrier of a mirror, or resting in a peaceful meadow with woven bamboo furniture, when, after this, I step out on to the square, my eyes are immediately assailed by the magnificent reality of the revolution.”

–Osip Mandelstam, Russian poet

1930s

“The Metropol is an old hotel in the center of Moscow. Some of the staff had been there since the days of the tsar. The shabby luxury of the carpeted lobby, the ornate brass carvings, the red plush and gilded furniture, and the gold-braided uniforms of the reception personnel contrasted sharply with the world outside… The staff never seemed to change. For ten, fifteen, twenty years the same elevator operator took me up to the top floor… For all I know, he is still there…”

–Mary Leder, American emigrant to Russia (in 1931) My Life in Stalinist Russia“Moscow’s Metropol bar is the focal point of a glittering bourgeois society in the dull setting of Proletarianism. It is just an alcove off the main dining room of the hotel, yet famous as the starting-point of many an American friendship, where roving drinkers from (at that time) dry America, fed up on the glories of building Communism and tourist glimpses of the Kremlin, rushed to quench their thirst and feast their eyes on the Soviet barmaids.

The barmaids in the big valuta hotels are of old Russian families, girls largely of aristocratic or bourgeois homes, who do not quite fit into office or more rigorous work. Theirs is a good job while it lasts because they are in close proximity to food from the restaurant and the kitchen. They meet no one but foreigners, and Russians love to come into contact with foreigners. They are to a considerable extent decoys, in that they report all significant conversations among foreigners to the GPU, and the danger of their position is that they might disclose more information than they receive, or be suspected of doing so…”

–James Abbe, American journalistic photographer, I Photograph Russia“With the abandonment of the unbroken workweek, and the establishment of a uniform day of rest every sixth day, pered-vihodnoy, ‘the eve of the free day’ became the big night at the hotel. Whatever remained of fashion and affluence in the capital congregated here every sixth night for a big feed, vigorous dancing, and a brief release from drabness. For the Russians who could safely indulge it, an evening at the Metropol was the next best thing to a trip abroad. What if the place was honeycombed with spies, marking off (for a little intimate interrogation sooner or later) the big spenders and those too chummy with foreigners? What if one evening’s entertainment cost a week’s wages? What if it called for a little discreet embezzling of official funds, an offense soon made punishable by death? There were enough Russians risking it to crowd the bourgeois island to capacity.”

–Eugene Lyons, United Press Correspondent, Assignment in Utopia“When they arrived at the Metropol, he helped the girls out of the car. The line outside the restaurant parted, and a doorman in a braided uniform opened the door for them, the headwaiter in his black suit appeared, a free table in the crowded room was found, and a waiter materialized…

There were plenty of girls in the restaurant with foreigners. Varya knew they were given fashionable clothes, rides in automobiles, and that they also got married and went to live abroad. She wasn’t interested in foreigners but in this restaurant, with its fountain and music and famous people all around her. Wasn’t it this she was trying to escape to from her dingy communal apartment?

The starched tablecloths and napkins, the glitter of the chandeliers, the silver and the crystal—the Metropol, the Savoy, the National, the Grand Hotel. Before, these had been nothing but names to her, a Muscovite born and bred, but now her hour had come. A girl from the Arbat, she was quick on the uptake, observant, and she didn’t miss a thing, especially the way the men eyed her and the women looked past her. They ignored her because she was badly dressed. Never mind, they’d take notice when she came back dressed more elegantly than the lot of them. She didn’t dwell on how she was going to get hold of new clothes. She wouldn’t sell her self to foreigners; she was no prostitute. And anyway, not everyone here was like that. Take the table over there: one bottle among the lot of them, they hadn’t got money, they’d come to dance. She’d find her own kind of company.”

–Anatoly Rybakov, Russian novelist, Children of the Arbat“My fearingly eyes explore “the Hotel Metropol” (never, in America, has this comrade stopped at a really “first class” robbinghouse. Studiously, in Europe, did he avoid the triplestar of Herr Baedeker…and now?) “Change, that’s all.” O plutocracy, O socialism—gird we up our loins: forward, into paradox…

At the sight of a flight of marble-or-something steps framed by boundlessly flowering plants we verily tremble: is (impossibly) the candle worth the game? And just as if to answer said unsaidness, down something-or-marble vista visionary with vegetation waddles 1 prodigiously pompous, quite supernaturally unlovely, infratrollop with far (far) too golden locks; gotup rather than arrayed in ultraerstwhile vividly various whathaveyous; assertingly (if not pugnaciously) puffing a gigantic cigarette; vaguely but unmistakably clutching, to this more hulking than that mammiform appendage, a brutally battered skeleton of immense milkcan… A not imposing counter. Behind it, a ½ bald notimposing clerk wailing DAs into a notimposing telephone. Above, around, unbelievable emanation of ex-; incredible apotheosis of isn’t. Thither, hauntingly hither, glide a few uncouth ghosts…”

–e.e. cummings, American poet, EIMIDiary

“News from Moscow is that the trial and execution for high treason, terrorism, and espionage of eight officials were officially announced including Karakhan, Yenukidze, Zukerman, and [“Baron”] Steiger.

Poor Steiger. He represented the Bureau of Cultural Relations or something of that sort. He was, in fact, a sort of liaison man, apart from the Foreign Office, between the Kremlin and the Diplomatic Corps. He invited some of the party to the opera for a special performance and thereafter took us to the ‘night club’ at the Metropol Hotel. Shortly after one o’clock he was tapped on the shoulder, left the table, did not return, and was never seen thereafter”.

–Joseph Davies, the 2nd US ambassador to the Soviet Union, Mission to Moscow“Have you come here alone or with your wife?”

“Alone, alone, I am always alone,” replied the professor bitterly.

“But where is your luggage, professor?” asked Berlioz cunningly. “At the Metropol? Where are you staying…?”<

“In your flat,” the professor suddenly replied casually and winked.

“I’m… I should be delighted…” stuttered Berlioz, “but I’m afraid you wouldn’t be very comfortable at my place… the rooms at the Metropol are excellent, it’s a first class hotel…”

–Mikhail Bulgakov, Russian novelist, The Master and Margarita (in which Satan arrives in Moscow in the guise of a professor…)

1940s

“[At the dinner celebrating the signing of the Ribbentrop pact, the Kremlinites’] swagger was so raffish that Ribbentrop said he felt as at ease as he did among old Nazi comrades. While the guests were chatting, Stalin went into the sumptuous Andreevsky Hall to check the seating plan, which he enjoyed doing, even at Kuntsevo. The twenty-two guests were dwarfed by the grandeur of the hall, the colossal flower arrangements, the imperial gold cutlery and, even more, by the twenty-four courses that included caviar, all manner of fishes and meats, and lashings of pepper vodka and Crimean champagne. The white-clad waiters were the same staff from the Metropol Hotel who would serve Churchill and Roosevelt at Yalta…”

–Simon Sebag Montefiore, historian, The Court of the Red Tsar“I thought about my first weeks in the Metropol Hotel in 1944… In wartime the grim and gloomy old hostelry had bulged with roistering and friendly newspapermen. There were twenty or thirty Americans and Englishmen alone and many other foreigners too. It was a poor night, indeed, when a party was not in progress in someone’s rooms and usually there were several to choose from. And the guests were not just foreigners. There were as many Russians as foreigners and often more. And not just party girls, attracted by the excitement of meeting foreigners, the chance of food and drink, a bath or a warm bed to sleep in. While I had, it is true, heard in those times a Russian say that no respectable Soviet citizen would permit himself to enter the Metropol, that was obviously pure snobbery. Because the day did not pass when well-known Russian artists and writers and singers, famous Party propagandists, proud holders of the Order of Lenin or the Order of the Red Banner of Labor, Red Army colonels and generals, scientists and publicists, playwrights and ballerinas, did not enter the Metropol.”

–Harrison Salisbury, New York Times correspondent American in Russia“I can’t seem to stay away from the Metropol: it is a highly colored small station in the somber world of the embassy where I live, and a relief from the painful world of my Russian friends. It’s a grubby joint but it’s lively and I have taken to dropping over almost every day to listen to the stories about the night before, or the ones that Alex Werth remembers from the first year of the war, or Henry Shapiro remembers from even further back. Then I wander up and down the corridors, looking for people to talk to.

The third floor is the most interesting: two Turkish diplomats who never seem to be at home have the rooms opposite the elevator; across the hall from them are two Japanese military attachés and, in an adjoining cubicle, their Japanese chauffeur. Next to him is a journalist of a neutral country who is very proud that his mistress was once the mistress to a group of Uzbeks. This lady laughs too loud and too much and is the reason why the repatriated Russian tenor, who lives next door with his family, spends his mornings demanding a new suite of rooms. Next to the Russian tenor is a recently arrived middle-aged American who works in our consulate…”

–Lillian Hellman, American playwright, An Unfinished Woman“The commercial restaurant in the Metropol is magnificent. A great fountain plays in the center of the room. The ceiling is about three stories high. There is a dance floor and a raised place for a band [which], incidentally, played louder and worse American jazz music than any we had ever heard…

Since everything in the Soviet Union, every transaction, is under the state, or under monopolies granted by the state, the bookkeeping system is enormous. Thus the waiter, when he takes an order, writes it very carefully in a book. But he doesn’t go then and request the food. He goes to the bookkeeper, who makes another entry covering the food which has been ordered, and issues a slip which goes to the kitchen. There another entry is made, and certain food is requested. When the food is finally issued, an entry of the food issued is also made out on a slip, which is given to the waiter. But he doesn’t bring the food back to the table. He takes his slip to the bookkeeper, who makes another entry that such food as has been ordered has been issued, and gives another slip to the waiter, who then goes back to the kitchen and brings the food to the table, making a note in his book that the food which has been ordered, which has been entered, and which has been delivered, is now, finally, on the table…”

–John Steinbeck, American novelist, A Russian Journal“The fog of suspicion and fear hung over Moscow like evening mist over a tamarack swamp. Nor was it confined to the Russians. Everyone, Russian and foreign alike, was infected to a greater or lesser degree. Even the smallest things which ordinarily would be ascribed to chance aroused suspicion in this fetid atmosphere. For example, I was given Room 393 at the Hotel Metropol, a gloomy cavernous chamber with a sagging balcony that overlooked a dark interior courtyard. To me it was just another Metropol Hotel room—dismal and depressing but somewhat cleaner and better furnished, like the hotel itself, than I would have expected in 1944. But my newspaper colleagues lifted their eyebrows when I told them. ‘Hummmm…’ One of them said. ‘Alec Werth’s old room… Very interesting.’

‘Why in heaven’s name is that interesting I asked.

My colleague whispered in my ear. ‘It’s all set up…Saves them the trouble of putting the microphones into a new room.’

Freshly arrived from the United States I snorted at this… But…when I finally moved out of the Metropol and vacated Room 393 it was given, in succession, to three other newspaper correspondents…”

–Harrison Salisbury, New York Times correspondent, American in RussiaDespite the fact that the Moskva was a new hotel and the largest, nothing in it worked as it should—it was cold, the faucets leaked, and the bathtubs, brought from Eastern Germany, could not be used because the drainage of water flooded the floor… I frequently recalled with envy my sojourn in the Metropol Hotel in 1944. Everything was old there, but in working order, and the superannuated help spoke English and French and demeaned themselves with grace and precision.”

–Milovan Djilas, member Yugoslavian Politburo, Conversations with Stalin